Across investment markets investors have always sought to diversify investments; to truly make that happen it’s thought investors should have what are known as ‘‘non-correlated’’ assets. The theory is that noncorrelated assets will move in the opposite direction to the rest of your portfolio when things get tough.

When market returns are negative, managers of non-correlated assets look for an inverse relationship or a positive return. However, technically managers of uncorrelated assets (while not necessarily boosting their returns) would more likely simply avoid losing money.

For example, if there was a stockmarket crash, the non-correlated assets should stay steady while share prices are plunging.

As market volatility has increased we have seen more fund managers presenting more alternative asset opportunities to the wealth management industry. Many hedge funds cite the non-correlated nature of returns to traditional asset classes. The non-correlated activities of the Future Fund, now chaired by former federal treasurer, Peter Costello, is often cited as a model.

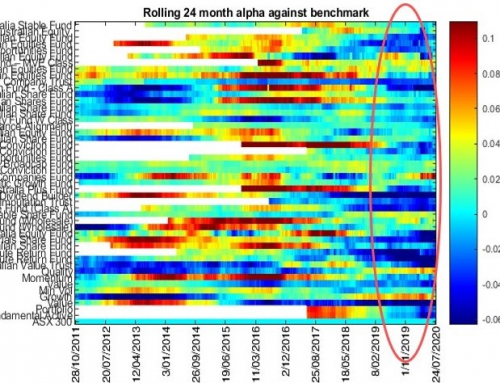

We have now entered a lower-return environment where market performance or Beta, a traditional measure of returns, has become expensive, and therefore the market is looking to generate Alpha, or excess return above the market.

Risk-adjusted returns are generally measured using the Sharpe ratio, which is the excess return above the risk-free rate or the cash rate, as it is assumed to have zero risk.

Why is correlation important for investors adjusting their strategy in changing times?

Stephen Romic from DFS Advisory Portfolio Solutions points out that “equity risk is the main risk that dominates all portfolios and interest rate risk associated with bond markets tends to be the dominant risk factor across the defensive part of portfolios.

“As forecasting future returns is problematic and challenging at best, it is sensible to construct diversified portfolios that reduce risk. In this context, reducing risk means allocating a part of the asset allocation to investment strategies that do not follow the direction of equity and bond markets, which generally dominate portfolios.”

Which is all very well, but a private investors has to consider a few points when comparisons are made with institutional managers — especially the $130 billion Australian Future Fund.

- Firstly, the Future Fund does not have liabilities or outgoings until 2025, therefore its time horizon is at least nine years. When they look at a certain investment strategy, investors must firstly ensure they are comparing apples with apples.

- The Future Fund has allocated 10 per cent of its assets towards private equity, which can be difficult to access for the private investor. Raphael Arndt, chief investment officer at the Future Fund, says the approach is to use PE to access “the innovation cycle and disruptive technologies” and stresses it is not “strongly correlated to listed equity markets”.

Arndt mentions the “high fees and poor alignment” that can exist in this space and emphasises the importance of analysis and understanding to provide exposure to managers with “appropriate terms and share an acceptable amount of the ‘alpha’ they generate with investors”.

- Non-correlated assets can be illiquid (you can’t sell them easily or quickly). Indeed, private equity, by its very nature, is equity as opposed to debt and investors must bear that in mind.

Separately, the Future Fund also has an allocation of 12 per cent to alternative assets. Again due diligence is stressed by Arndt, with an emphasis on “true uncorrelated returns and doing so with reasonable fees and liquidity “.

While professional wealth managers emphasise the investment cycle as the period an investor should approach investment returns, the reality is that many investors approach the period as three years. Arndt does suggest alternatives need a longer-term time frame.

Another perspective on alternative assets comes from Stephen Brown of Monash University and the Stern School of Business at New York University. Brown highlights a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio has a 10-year annualised return of 6.6 per cent against 5.6 per cent for hedge funds.

Despite this, Brown advocates a small allocation towards hedge funds (5 per cent) and says they do reduce financial risk. Yet many wealth managers underappreciate the due diligence needed to understand the operational risks, and recognise that diversification alone is not sufficient to mitigate such risk. So unsophisticated investors can fall into the trap of chasing past returns.

Romic has a counter to Brown’s argument and points out that “equity markets offer the greatest upside potential as they come with the highest level of risk. If uncorrelated investment strategies are reducing exposure to equity markets, then it follows that they cannot expect to outperform equity markets over the long term. We see uncorrelated investment strategies playing a defensive role; it’s a portfolio diversifier and certainly not a return chaser.

“Such portfolios of uncorrelated investment strategies are increasingly becoming attractive in the current environment where cash and bond yields are at historically low levels.” He goes on to point out that a portfolio of multiple investment strategies (uncorrelated to equity and bond markets and uncorrelated to each another) must have the potential and expectation of outperforming cash over a complete cycle. If they don’t then the default quickly becomes cash.

Will Hamilton is managing partner of Hamilton Wealth Management, a Melbourne-based independent wealth manager.will.hamilton@hamiltonwealth.com.au

Disclaimer